A Brief History of My Relationship with Weezer’s “Pinkerton”

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of its release

The details of that night are fuzzy, but I remember it was bitter cold. I was probably home from college for Christmas, so let’s say it was December 1998. Roughly two years and some change after Weezer released its sophomore effort to anemic sales and general bafflement. And roughly two years and some change before “Island in the Sun” became a radio hit and revived the band’s prospects.

My friend Kelly was driving me home from the movies, and we were desperately waiting for the heater to start blasting something other than cold air. “Flip through my CDs and find something,” she says to me.

You see, back then, people kept these massive booklets of compact discs in their cars.

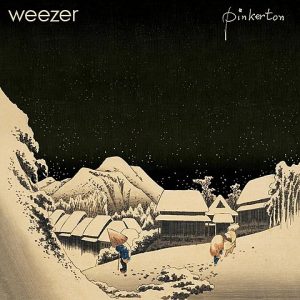

A few pages in, there it was: That bewitching black-and-sepia cover art, looking like some 19th-century Japanese woodcut print (because, in fact, that’s exactly what it is).

I’d read Rolling Stone’s 3/5-star review when the album came out. The description didn’t especially make me want to listen to it, even though I owned the Blue Album. But I remembered the cover art. And the title intrigued me.

“Is this that Weezer album that’s, like, based on Madame Butterfly or something?” I asked Kelly. “Is it any good?”

“Oh yeah!” she said. “I haven’t listened to that in forever. It’s good, I think.”

We made it through “Tired of Sex” and about 30 seconds of “Getchoo.”

“Um … I think I must have been thinking of a different album,” Kelly said as she hit the eject button.

But I liked it, even though it was not the type of music I liked at the time.

I still didn’t listen to all of Pinkerton, start to finish, until critics started to re-evaluate it in the mid-’00s as an influential, proto-emo offering. Rolling Stone decided that, actually, maybe Pinkerton was a 5-star album after all. With my rapidly approaching quarter-life crisis, all of Rivers Cuomo’s self-loathing and romantic awkwardness resonated with me.

The folk-rock band I was in started covering “Butterfly.” The more we played it, though, the more the line “If I’m a dog then you’re a bitch” made me cringe.

On the Fourth of July, I banged out a version of “The Good Life” on my acoustic guitar while we were waiting for the fireworks to start. When it was over, my mother—who taught me to play guitar and was always willing to indulge me when I wanted to share some new band with her—sighed. “Wow,” she said, “that’s a really dumb song.”

Thus has it always been with Pinkerton. It’s entrancing and off-putting, relatable and alienating, a failure and a classic.